Richie Morris, 21, of Portland, had to wait nine months to see a therapist after moving from New Hampshire to Portland in 2023. “It’s extremely disheartening,” they said. Ben McCanna/Staff Photographer

Tessa Buckley is on a waitlist for in-home mental health services for her 10-year-old son, who suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety.

It might take two years for him to reach the top of the list.

“It can feel defeating,” said Buckley, 32, of southern Maine.

Richie Morris, 21, of Portland, had to wait nine months to see a therapist after moving from New Hampshire to Portland in 2023 before finally finding mental health counseling in January.

“Everyone either had a super-long waitlist, only accepted self-pay or didn’t take my insurance,” said Morris, who has depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder. “It’s extremely disheartening and makes you want to give up hope. I started to think, ‘Am I always going to feel this way?’ It makes you feel like there’s no options in life.”

Access to mental health care is at a crisis point in Maine. And experts say it’s unclear if it’s going to get better anytime soon, even though the Mills administration and Maine lawmakers invested millions in mental health during this spring’s legislative session.

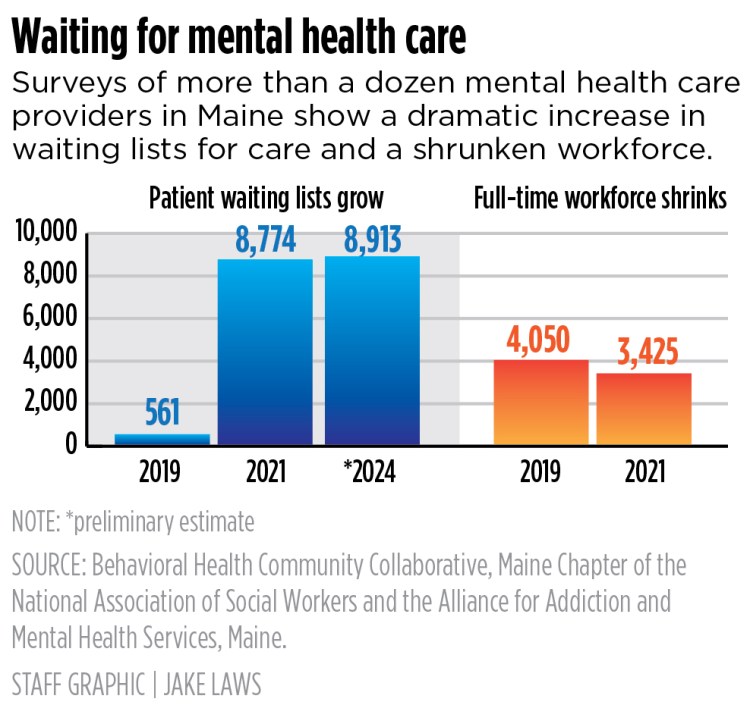

Surveys of behavioral health providers reveal a dramatic increase in mental health waitlists in Maine since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, a crisis of access at a time of burgeoning demand. As waitlists have ballooned, calls to the state’s crisis lines have increased by 30% from prepandemic rates.

The problems have been exacerbated by worsening mental health for many since the start of the pandemic, coupled with an acute shortage of staff at behavioral health providers.

The pandemic caused people to feel isolated as events were canceled, school went virtual for many and gatherings were limited. And even though the public health emergency ended in May 2023 and activities largely returned to prepandemic levels even before then, mental health challenges persist.

Maine’s mental health system has faced increased scrutiny since the Lewiston mass shooting in October. Robert Card, who shot and killed 18 people at two locations in Lewiston, had been hospitalized for psychiatric reasons for two weeks the summer before the tragedy and displayed signs of acute mental health problems and potential for violence in the weeks and months before the shootings.

The mass shooting prompted the Mills administration and Maine lawmakers to invest heavily in the state’s mental health system during the legislative session that ended in the past few weeks, and to push through a number of gun safety reforms.

But Malory Shaughnessy, executive director of the Alliance for Addiction and Mental Health Services, Maine, which represents nonprofit providers, said lawmakers and the Mills administration missed an opportunity to make the sort of substantive changes that would have improved access to care for thousands of Maine people who need it.

“I’m disappointed that we didn’t do more to foundationally invest in our system of care,” Shaughnessy said.

DEMAND SPIKES AS CAPACITY SHRINKS

The inability to get timely mental health can take a toll on families, as well as on individuals who need the help.

Tessa Buckley’s son Finn has been receiving outpatient therapy since he was hospitalized last year. But Buckley said it is hard to wait for the more intensive care he needs while knowing that timely services are crucial.

“It would be good if we could have the services when we really need them,” she said.

Buckley lives in southern Maine but did not want to disclose exactly where she lives because of a past relationship.

Elv Jopling, of Sanford, knows the value of timely care and could have been in a precarious situation today if not for a lucky break.

Elv was hospitalized for suicidal ideation in 2022 and might still be waiting for care if someone at the hospital hadn’t told Elv’s family about a mental health nurse practitioner who was starting up a new practice. The 16-year-old sophomore at Sanford High School is now doing much better with the help of an effective outpatient therapy program.

Elv Jopling, 16, near his home in Sanford on April 24. Elv has been hospitalized and in crisis centers three times for mental health issues but is doing better now with the help of effective therapy. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

“Honestly, I don’t know if I would be here right now,” Elv said. “I’m happy I did get help, because problems don’t last forever, and you can always learn ways to deal with them.”

A February 2022 survey by Maine’s Behavioral Health Community Collaborative of 17 providers shows that the number of people on behavioral health waitlists – for substance use disorder treatment and mental health services – skyrocketed from 561 in 2019 to 8,774 at the end of 2021.

Preliminary results from a similar survey in 2024 show the problem has only gotten worse, with 8,913 clients waiting an average of 32 weeks – or more than half a year – for mental health counseling services, according to the Maine chapter of the National Association of Social Workers and the Alliance for Addiction and Mental Health Services, Maine.

“There’s been this huge increase in usage and need for behavioral health care,” Shaughnessy said. “But the resources and the workforce are just not growing fast enough to meet the growing need.”

And in another sign of high demand, calls to Maine crisis lines operated by The Opportunity Alliance have jumped 30% since 2019, with 117,000 calls in 2023.

Rosalie Genova, a Portland counselor specializing in substance use disorder and mental health, said she’s taken on more cases than she would prefer. She has 28 patients, nearly double her ideal number of 15 to 17. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

Rosalie Genova, a Portland counselor specializing in substance use disorder and mental health, said she’s taken on more cases than she would prefer. She has 28 patients, nearly double her ideal number of 15 to 17. But there is so much demand for help and so little capacity that she finds it hard to turn away people who have tried for many months or years to gain access to mental health counseling.

Some counselors refuse to work with insurance carriers, requiring all payments to be out of pocket, which further constricts access to affordable care, she said.

“Mental health can continue to deteriorate if it’s not being addressed,” Genova said. “It can really be discouraging to people. It’s not personal, but people can feel that they are not cared for by the community.”

And, Genova said, the “cost-benefit analysis” for those thinking of going into mental health work – including office assistants, medical technicians and clinicians – is weak, making other careers more attractive.

“It’s not a very good deal right now (to work in mental health),” Genova said. “Every position is difficult to (fill).”

Residential treatment and intensive in-home care are especially hard to secure.

Katie Fullam Harris, chief government affairs officer for MaineHealth, which operates Maine Medical Center in Portland and a large network of health care providers across the state, said many adolescents spend too much time in Maine’s hospitals because there aren’t enough alternatives.

“There is not an appropriate level of care to meet their needs,” Harris said. “Many need secure residential treatment or very intense in-home supports, neither of which exist in Maine. Three hundred and forty-five kids spent more than 48 hours in a MaineHealth ER awaiting appropriate disposition for mental health.”

Overall, there were about 11,500 visits to emergency departments across Maine in 2023 for conditions related to potential suicide attempts or suicidal ideation, according to state data. ER visits for suicidal ideation have been relatively steady over the past five years, when the state first began recording the statistic.

Elv Jopling, right, and his sister Lizzy Jopling, 11, near their home in Sanford late last month. “I’m happy I did get help, because problems don’t last forever, and you can always learn ways to deal with them,” Elv said. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

The lack of access to care is a national problem, and getting help is even more difficult in many other states.

According to a 2023 Forbes Advisor analysis, Maine ranked sixth-best in the nation for access to mental health, even though 30% of youths in the state “who had a major depressive episode in the past year did not receive mental health services.” The worst state for access – Texas – reported that 73% of youths did not get needed mental health services.

Maine had the 16th-highest rate of suicide among the 50 states in 2021, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the second-highest rate in New England, with Vermont being the highest. Maine had 19.5 suicides per 100,000 residents, while Massachusetts, with the third-lowest rate of suicides nationwide, had 8 per 100,000.

MAINE’S RESPONSE TO LEWISTON TRAGEDY

Dr. John Campbell, vice president and senior physician executive at Northern Light Acadia Hospital in Bangor, a psychiatric hospital, said shortcomings in mental health have been “dragged out into the light of day” since the Lewiston tragedy.

“Never have we had more open public conversations about what we need and what is not working in the system,” Campbell said. “There’s no more denying it. It is now front and center. We need bigger front doors and shorter corridors to get you to what you need.”

But the end results of the recent legislative session were mixed, critics say.

Shaughnessy, of the Alliance for Addiction and Mental Health Services, Maine, said a suite of bills promoted by mental health advocates included proposals that either weren’t approved by the Legislature, didn’t get funded or were funded at a fraction of what was requested. Some would have resulted in increased pay for those working in the field.

Shaughnessy said a major flaw in the Mills administration’s response has been not investing in higher reimbursement rates for care providers that would permanently boost wages and benefits. One-time funding is not going to help solve the problem, she said.

Maine Health and Human Services Commissioner Jeanne Lambrew said that while there’s still more to be done to address the mental health crisis, significant progress is being made, including $34 million in investments in behavioral health in the 2024 supplemental budget. She said new investments in affordable housing also should help attract workers in all sectors of the economy, including health care.

“The way to address this crisis is to give people someone to call, have someone ready to respond and give people somewhere to go,” Lambrew said.

Lambrew, who is set to leave the Mills administration at the end of May, said Maine has made investments on all three fronts.

This year, the supplemental budget includes funding to expand the number of mobile mental health units that respond to people in crisis at their homes, to add additional crisis receiving centers to help ease emergency department usage by giving people a place to go and get connected to services, and to cover startup costs for 11 new community behavioral health centers. The health centers are similar to federally qualified health clinics – and can access federal funding – but are geared specifically for behavioral health.

The goal of all the investments is to improve mental health access and prevent major psychiatric episodes that lead to emergency department hospitalization.

Lambrew said she understands why critics say the response hasn’t been “fast enough or good enough,” but she said the state is trying its best to improve services and “stay ahead of the wave.”

The crisis receiving centers, mobile crisis units and community mental health clinics should help to prevent some of those in crisis from going to hospital ERs, which should help ease the strain, she said.

She said housing investments and other efforts to boost the workforce, such as tuition reimbursement programs, should also help improve access to services.

It’s difficult to know exactly how many people are employed in the mental health workforce because many positions overlap with others in the health care sector. But the overall number of health care practitioners in Maine has shrunk since the start of the pandemic, according to federal data.

The health care practitioner workforce in Maine – including doctors, nurses, psychiatrists, counselors, therapists and other front-line health workers – fell from 43,290 in 2019, a peak after years of steady growth, to 40,670 in 2023, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Meanwhile, Maine’s population has grown by more than 2% since 2021, at a much faster pace than the previous decade.

Federal labor statistics can lag and may not reflect the impacts of recent reforms. Lindsay Hammes, a Maine DHHS spokeswoman, said that since 2022, thanks to Mills administration investments from the federal Jobs and Recovery Plan, the overall health care workforce has increased by about 10% when looking at the entire health care workforce.

Maine’s health care network and education system also are working on ways to expand mental health services, apart from the initiatives passed by lawmakers this spring.

The University of New England is launching a new psychiatric nurse practitioner degree program, which will enroll 15 students per year.

Northern Light has increased the number of psychiatrists through an in-house educational program and opened the James and Hilla Bruni Family-Centered Integrated Behavioral Health Program in 2022 on Mercy Hospital’s Fore River campus.

Dr. Christopher Pezzullo, a pediatrician with the Mercy Health Center in Portland, photographed at the Bruni Center, a new pediatric mental health service at the health center. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

With the new Bruni center, pediatricians can get adolescents into therapy much more easily than they could before, said Dr. Christopher Pezzullo, a Portland pediatrician whose office is located in the same building.

“Before, if we had a patient who really needed to urgently see a behavioral health provider, we were left with very few options,” Pezzullo said. “Often, the wait was months. Now, they can get into care quickly. I can even go across the hall and see if one of the counselors is available that day.”

MaineHealth, the state’s largest health network, has expanded behavioral health services into its primary care offices over the past several years, aiming to make counseling and other services more accessible.

Still, the path to care and recovery can be long, even for those lucky enough to get help.

Stephanie Jopling, Elv’s mother, said it took a lot of work to improve Elv’s condition – stabilizing his mental health and eliminating his suicidal ideations – once he got the care he needed. Elv was hospitalized twice and spent time at two non-hospital crisis centers before being able to get into therapy.

“It was disheartening to think, ‘What if nobody had been able to help?’ ” Jopling said. “I don’t know what we would have done.”

« Previous

Related Stories